| Disparate authors such as Celsus, Vitruvius,

Pliny, Frontinus, Columella, Varro and Vegetius, show the Roman concept of

health interwoven with the normal life and ordinary process of government

in the Roman Empire. Vitruvius, a practicing architect in the milieu of

the Roman Empire, shows through his writing how important sanitary

planning was for public buildings. His chapter on city planning begins

with a discussion of the salubrity of sites and throughout this section

the influence of the Hippocratic tract Airs, Waters, Places is

apparent:

“In the case of the walls these will be the main points: First, the

choice of the most healthy site. Now this will be high and free from

clouds and frost, with an aspect neither hot nor cold but temperate. In

this way a marshy neighborhood will be avoided. For when the morning

breezes blow towards the town at sunrise, as they bring with them mists

from the marshes and, mingled with the mist, the poisonous breath of the

creatures of the marshes [i.e., microorganisms], to be wafted into the

bodies of the inhabitants, they will make the site unhealthy.” (De

Architectura I.2-5) |

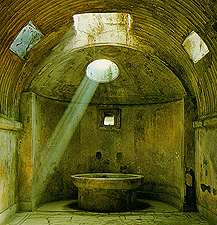

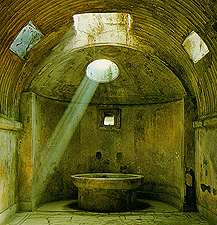

Forum Baths, Pompeii, first century BCE Caldarium

One of the characteristic Imperial Roman building types is the giant

bath complex which could house not only bathing facilities but lecture

halls, gymnasia, libraries and gardens. Roman bathing establishments

usually provided three kinds of baths, i.e., hot, tepid and cold. The room

pictured above was kept warm by hot air circulating through pipes in the

walls and floor. |

The skull is

symbolic of man’s fate and reminds us of the frailty of human existence. Rather

than shrink from signs of death, the Romans seem to have employed them as

reminders to “seize the day”. This particular mosaic was used as a tabletop.

There are many extant examples of cups and dining areas adorned with skeletal

motifs. In Petronius’ Satyricon, in the middle of a great banquet, a slave

brings in a silver skeleton put together with flexible joints, and after it was

flung on the table several times, the host Trimalchio recited: Man’s life,

alas, is but a span So let us live it while we can, We’ll be like this when

dead. Despite the advanced state of sanitation engineering in the Roman

world, the average life span was only 30-40 years.

The skull is

symbolic of man’s fate and reminds us of the frailty of human existence. Rather

than shrink from signs of death, the Romans seem to have employed them as

reminders to “seize the day”. This particular mosaic was used as a tabletop.

There are many extant examples of cups and dining areas adorned with skeletal

motifs. In Petronius’ Satyricon, in the middle of a great banquet, a slave

brings in a silver skeleton put together with flexible joints, and after it was

flung on the table several times, the host Trimalchio recited: Man’s life,

alas, is but a span So let us live it while we can, We’ll be like this when

dead. Despite the advanced state of sanitation engineering in the Roman

world, the average life span was only 30-40 years.