Woodcut illustration from a Venetian edition of Galen's works, 1550

If the work of Hippocrates can be taken as representing the foundation of Greek medicine, then the work of Galen, who lived six centuries later, is the apex of that tradition. Galen crystallised all the best work of the Greek medical schools which had preceded his own time. It is essentially in the form of Galenism that Greek medicine was transmitted to the Renaissance scholars.

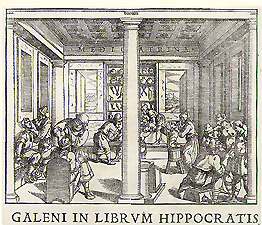

Woodcut illustration from a Venetian edition of Galen's works, 1550

Collection Bertarelli, Milan Medicatrina, Clinic Scene (above) This illustration accompanying Galenís work shows the surgical procedures described by Galen--on the head, eye, leg, mouth, bladder and genitals--still practiced in the 16th century. |

Galen hailed from Pergamon, an ancient center of civilization, containing, among other cultural institutions, a library second in importance only to Alexandria itself. Galenís training was eclectic and although his chief work was in biology and medicine, he was also known as a philosopher and philologist. Training in philosophy is, in Galenís view, not merely a pleasant addition to, but an essential part of the training of a doctor. His treatise entitled That the best Doctor is also a Philosopher gives to us a rather surprising ethical reason for the doctor to study philosophy. The profit motive, says Galen, is incompatible with a serious devotion to the art. The doctor must learn to despise money. Galen frequently accuses his colleagues of avarice and it is to defend the profession against this charge that he plays down the motive of financial gain in becoming a doctor. Galenís first professional appointment was as surgeon to the gladiators in Pergamon. In his tenure as surgeon he undoubtedly gained much experience and practical knowledge in anatomy from the combat wounds he was compelled to treat. After four years he immigrated to Rome where he attained a brilliant reputation as a practitioner and a public demonstrator of anatomy. Among his patients were the emperors Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus, Commodus and Septimius Severus. |

GALENISMGalen, for all his mistakes, remained the unchallenged authority for over a thousand years. After he died in 203 CE, serious anatomical and physiological research ground to a halt, because everything there was to be said on the subject had been said by Galen, who, it is reported, kept at least 20 scribes on staff to write down his every dictum. Although he was not a Christian, Galenís writings reflect a belief in only one god, and he declared that the body was an instrument of the soul. This made him most acceptable to the fathers of the church and to Arab and Hebrew scholars. Galenís mistakes perpetuated fundamental errors for nearly fifteen hundred years until Vesalius, the sixteenth century anatomist, although he regarded his predecessor with esteem, began to dispel Galenís authority. |

|