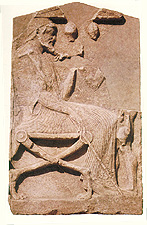

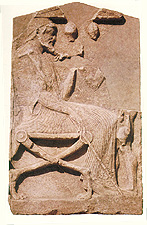

Fragment of a grave stele, Ionian, 5th century BCE: East Greek

Tombstone of a Doctor

This tombstone is identifable as belonging to a doctor by the two

small cupping vessels which appear at the top of the stele. Because the

marker is damaged, we cannot know whether the figure standing at right was

a patient or assistant. |

Health was isonome, “equality before the law”, among these fluids, and

illness monarche, the dominance of one of them. This conception was taken

from the observed struggle of factions in politics. Among the many

qualities that needed to be held in balance were heat and cold, moisture

and dryness, bitterness and sweetness. This doctrine was later parlayed by

Hippocrates into the Theory of the Four Humors, which provided the basis

for medical theory up until the time of the American Revolution.

The philosophers/physicians Empedocles and Anaxagoras were

contemporaries of Alcmaeon. Like other scientists of their day, they

inquired about such quasi-medical topics as the composition of matter (is

the primary element earth, fire or water?), the seat of the human soul

(some believed it to be the heart, some the liver and still others the

diaphragm), and the procreative process of humans (most held that the male

sperm was exclusively responsible for conception). Modern scientists have

grappled with these same problems with only slightly more success than did

the Greeks. We know that atoms constitute matter and that atoms are

further divided into protons, and protons into quarks; but what smaller

constituents await discovery? The fact that 2,500 years later we are still

asking some of the same questions posed by the Greeks brings to mind the

phrase nihil sub sole novi, that is, “there is nothing new under the sun”

(Eccl.i.9). For every question we may posit, the Greeks have surely asked

and answered it.

|

as well as

physicians and the distinction between the two fields was often blurred. At its

inception in the sixth century BCE, ancient medicine was a mere branch of

natural philosophy. Even in Late Antiquity, when the philosopher/physician Galen

reigned supreme, philosophy was considered a necessary part of medical training.

Unlike philosophy and medicine, which worked in harmony, the tension between

medicine and religious belief often stifled or impeded physiological research.

Throughout antiquity, rational medicine and faith healing existed side by side,

never fully divorcing themselves from one another Roman medicine especially was

an eclectic blend of rational Hellenistic medicine, folk remedies and religious

cult practice. Like so many other aspects of antiquity, medicine was truly

interdisciplinary, influencing and in turn being influenced by art, literature,

philosophy, politics and in no small way, religion.

as well as

physicians and the distinction between the two fields was often blurred. At its

inception in the sixth century BCE, ancient medicine was a mere branch of

natural philosophy. Even in Late Antiquity, when the philosopher/physician Galen

reigned supreme, philosophy was considered a necessary part of medical training.

Unlike philosophy and medicine, which worked in harmony, the tension between

medicine and religious belief often stifled or impeded physiological research.

Throughout antiquity, rational medicine and faith healing existed side by side,

never fully divorcing themselves from one another Roman medicine especially was

an eclectic blend of rational Hellenistic medicine, folk remedies and religious

cult practice. Like so many other aspects of antiquity, medicine was truly

interdisciplinary, influencing and in turn being influenced by art, literature,

philosophy, politics and in no small way, religion.